The Scrapbook

Full list of Stories

Storytelling is what makes us human. It tells us where we’ve been, who we are, and what we might accomplish. I’ve always been a big fan of the process, and over the years, I’ve been lucky enough to practice it quite a bit.

Below are some of my personal favorites - both in Missouri (home turf), the less-known history of the U.S. (just for funsies), and one or two places I’ve visited. Videos and transcripts are below. More resources can be found on the “Links” page.

I also visit presidential sites every so often. You can find those on the “Presidential Sites” page.

Stick around! Maybe you’ll find something you like.

The Horrors of Coldwater Creek

This little stream in northern Saint Louis is called Coldwater Creek. It starts at around the airport and travels 19 miles until it reaches the Missouri River, and in 1989, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers - or USACE - was working on a flood control project on the creek with the local communities. The local communities, by the way, are St. Ann, Hazelwood, Florissant, Old Jamestown, Black Jack, and Spanish Lake. One day in 1989, they were forced to stop working, due to a report that came out by the Department of Energy - or DOE - that claimed there was radioactive material in and around Coldwater Creek. Now these rumors aren’t new - people had claimed for years that there was something in the water. But the government said the area was safe, so a lot of people went about their lives. But now enough people in the area were getting sick - cancer sick - that the DOE decided to step in. And what did they find?

Let’s take a step back.

In World War Two, the U.S. Energy Department hired a company named Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals to produce uranium for the Manhattan Project. Making uranium creates a byproduct of radioactive waste, by the way, and you can’t just throw that away. So what do you do with it?

In 1947, Mallinckrodt and Missouri Energy District created the Saint Louis Airport Storage Site, or SLAPS, on the northern border of the airport. At that point, the only people really living up around the airport were the families of people contracted to work on planes and vehicles during WWII. But there were still enough people around for them to know what they were doing - and due to a 1946 memo that said the material was so toxic that it posed a threat to workers, these organizations did know what they were doing. Mallinckrodt stored waste there from 1949 to 1966, and they transported the radioactive waste from the plant to the site in uncovered dump trucks, one of which crashed and spilled its load in Hazelwood in 1953. Local firefighters hosed away the waste and told everyone it was safe.

In 1965, a survey of SLAPS showed that twenty years of refined uranium had created 120,000 tons of radioactive waste. Mallinckrodt decided to stop processing uranium in Saint Louis, bury the facilities at the SLAPS site, and sell part of the radioactive material to the Cotter Corporation, which buried it in two places - Latty Avenue in Hazelwood in 1966, and the West Lake Landfill in 1973. It’s important to note that a) this was still being transported in uncovered trucks, b) burying radioactive material in the ground does not make it less dangerous, and c) they didn’t have permission to dump radioactive material at West Lake. This was illegal.

At the site of Latty Avenue, material was processed and eventually shipped somewhere else, which also doesn’t make the area more safe now that it’s gone. Radioactive waste from the SLAPS and Latty Avenue sites made it into the ground, and into Coldwater Creek, and I don’t need to tell you how bad this already is, right? Ground contamination is really bad, but water contamination means the radioactivity moves even faster. It’s also worth noting at this time that…I didn’t tell the whole truth earlier. It wasn’t JUST families of servicemen living in the area. Saint Louis has a strong black population that, through generations of segregation, had moved to the north part of the city and county. In the 1970s, partly due to the failed Pruitt-Igoe project (which I’ll do another video on later), a large number of black residents moved into the areas near the creek, namely Spanish Lake. I could write a book and a half on racial tensions just in Saint Louis, which I won’t. But just so you know, that’s a component here as well.

So - 1989 - DOE comes out with a report that Coldwater Creek’s radioactive. They trace the material to the dump sites, which points to Mallinckrodt. Again, the government and the companies knew there was material in and around the creek, but they considered it, quote, “a safe amount.” This is the first time somebody’s actually come out and said “...maybe it’s not a safe amount, though.”

In 1990, the EPA puts the entire 19-mile creek on its list of Superfund sites. Quick side note - Superfund is a program that helps clean up sites that are contaminated with hazardous materials. This isn’t terribly relevant, but there are more than 1,300 active Superfund sites in the nation, 33 in Missouri, and 9 in the Greater Saint Louis area. You wanna have a REALLY bad day? Go find the one that’s closest to you!

In 2004, Mallinckrodt employees who worked with the uranium become eligible for compensation IF they can prove how much radiation they were exposed to at the time - I have no clue how you’d prove this. Sound off in the comments if you do.

In 2006, the EPA proposes clean-up plans for two parts of the West Lake Landfill, and in 2008, they actually make the clean-up plans and show them to the communities. The communities hand it back and say “you need to be WAY more specific with how you’re gonna do this,” and the EPA says “ok!” and gets back to work. During this time, more and more people are noticing an alarming increase in cancer rates, birth defects, etc.

In 2010, an underground fire breaks out at the West Lake landfill a quarter mile away from the radioactive material, which gets everyone’s attention again - for a while. As of 2023, the fire’s still being contained. In 2012, the CDC says the USACE was working downstream from the waste sites and noticed a large level of contamination, so they started an investigation. In 2014, the West Lake landfill installed an extraction system to control the toxic fumes from the fire, and over the next couple years, the USACE and CDC confirmed a link between the communities’ health problems and the creek. They also found low levels of a radioactive chemical at a park near a *sigh* a grade school in the Hazelwood school district.

In 2018, A DECADE LATER, the EPA comes out with its revised cleanup plan. Over the next couple years, they work with the landfill to more clearly define their revised cleanup plan.

In 2022, radioactive material was found at the edge of the elementary school - the USACE tested it, and said it’s no more dangerous than other schools. The same year, a private company tested it and said “actually, it is dangerous.” The Hazelwood school district closed the school and relocated students - the USACE, by the way, was still saying the place was safe. In 2023, the U.S. Senate passed a bill for a federal clean-up of the school, which they turned into a storage facility.

In July 2025, Harvard published an extensive study revealing that if you live within one kilometer of Coldwater Creek - not “lived” or “used to live,” but “live,” present tense - you have a 44% higher risk of overall cancer. Further information on all this can be found at the links on my website, along with the transcript of this video. The same year - this year - the EPA rolled out another revision of its plan. After 18 years of dragging their feet, they announced making the waste sites and Coldwater Creek safer will finally break ground…in 2027.

Links to my research, additional information, and awareness groups can be found below. Special thanks to local news affiliates NBC, NPR, and Fox. (This video and transcript are purely for educational purposes, and not for profit.)

Coldwater Creek Facts (also, maybe click this one)

EPA — Superfund Homepage

EPA — Coldwater Creek-related Superfund sites documents

Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health — 2025 Survey

Just Moms STL (if there’s one link you click, it should be this one)

Missouri Coalition for the Environment — Historic Timeline of Toxic Waste in St. Louis

Missouri Independent — St. Louis Radioactive Waste Records

Washington’s First Crossing

If you know anything about George Washington, you probably know this picture.

“Washington Crossing the Delaware,” Emmanuel Leutze, 1851.

The man’s in charge of the nation’s first real army. He’s going up against the bigger, badder British Army, so he throws a Hail Mary and crosses the Delaware River on Christmas Eve, 1776, to sneak up and smack the British in their pasty little faces. And it works! They kick the British out of Trenton, New Jersey.

But one of my favorite stories about - well, about any president - is the other time Washington crossed a river.

It’s 1753 - 23 years earlier. We’ve got all thirteen colonies, but they still identify as British - and there’s already a lot of drama ‘cause they’re not treated as properly British, but that’s another story. What’s important is that the British are butting heads with the French for who gets what land. The French, by the way, are buddying up with native tribes for a strategic advantage, to which you say “wait, is this the French and Indian War?”

That starts the next year, so we’re getting close!

Behind the Allegheny Mountains in Pennsylvania is the Ohio River Valley, which both the British and the French claim. Part of the Ohio River Valley was claimed by the colony of Virginia - not the state of Virginia, the colony, that’s important - whose governor was a fella by the name of Robert Dinwiddie. Dinwiddie asks the Crown if he can warn the French that he’s gonna kick ‘em out of the Ohio River Valley - and then, you know, if they refuse, actually kick ‘em out of the valley. The Crown writes back and says “worth a shot!”

Robert Dinwiddie.

Dinwiddie writes what I’m sure was a very passive-aggressive letter to the French commanders at Fort Le Boeuf, up in what’s now the top corner of Pennsylvania near Lake Erie. He tells ‘em to clear out in the name of the king, and he needs someone to go take the letter from Williamsburg, Virginia to Fort Le Boeuf. But here’s the thing: in 2025, with the beauty of modern roads…that’s an eight-hour drive. In 1753, there weren’t any roads to the fort - the French had just gone down from Lake Erie, which isn’t anywhere near Williamsburg. What IS between the fort and Williamsburg is a hundred miles of Allegheny mountains. AND it’s late October. So whoever’s gonna deliver the letter’s gotta do some serious off-roading…in dead winter.

Lucky for Dinwiddie, the equivalent of that tall quiet kid you went to high school with who went hiking a lot…he pops up and volunteers.

George Washington, early twenties.

George Washington is 21. He’s a land surveyor who wants to join the British Army, which kind of also makes him the ROTC kid you knew in high school. (Shocking, I know.) People aren’t exactly lining up for this gig, plus George knows a couple important people and his older half-brother was an officer, so Dinwiddie gives him the letter and sends him on his way on October 31st.

Now George doesn’t speak a lick of French or any native languages, so along the way he picks up a frontiersman named Christopher Gist who does speak French, and the two turn their coats up and head into the Appalachian wilderness.

I’m not gonna go into details here, so if you’re wondering why I’m not mentioning Half-King or Logstown or anything like that, maybe I’ll do another later. What’s important is that George and Christopher made it to Fort Le Beouf on December 11th - six weeks later. George gave the commander the letter telling the French to leave the valley, the commander lets them stay and rest up for a few days, and eventually gives them the response letter, which says…”thanks, but we’re not going anywhere.”

(Sigh) So now they gotta go back.

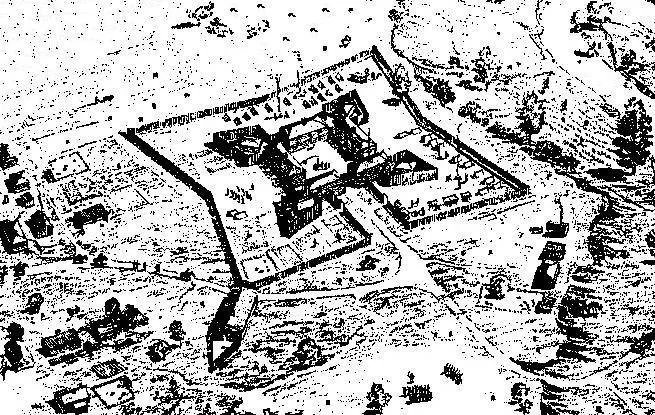

Fort Le Boeuf.

Again, I’m glossing over the details, but now we’re in late December and the weather’s bad. And their native guide had tried to shoot them out of nowhere, so they kicked him out and hiked another day till they got to the bank of the Allegheny River. Now, they weren’t too worried about crossing, ‘cause it’s late December and the weather’s bad, so the river’s frozen. Right?

(Sigh) Nope! It’s only frozen on the edges. The middle’s moving fast, and it’s carrying big chunks of ice down the river. But it’s only morning, so they have time to think of something. They have a hatchet, so - and this would’ve never crossed my mind - they chop down some small trees and build a raft. And to clarify, this is less “boat” and more “logs tied together.” It still takes them all day.

After the sun goes down, they finally slide the raft across the ice on the banks, hop in, and try to use poles to row to the other side of the river. It…didn’t go well. Washington later wrote:

“Before we were half way over we were jammed in the ice and in such a manner that we expected every moment our raft to sink and ourselves to perish.”

George Washington and Christopher Gist crossing the Allegheny River, Daniel Huntington, mid-1800s.

The ice is smashing in on all sides. Their raft is starting to fall apart. They need to try and stop so the ice can pass by. So George puts his pole in front of the raft to stop it. The raft smashes against the pole, which throws it into the water…along with George.

(Hypothermia depends on a lot of different factors we don’t always have, but we’re guessing it would’ve set in for George within a few minutes.)

George manages to grab the edge of the raft, and Christopher pulls him back on board. But depending on who you ask, the raft is either about to capsize, or falling apart. They can’t make it to the other side. And they can’t make it back to where they came from. Fortunately, they spot an island a little ways downstream. So they give up on the raft and make it to the island, where they spend what I assume is a freezing cold and nerve-wrecking night. Because what it comes down to it…you still don’t know how you’re gonna make it to the other side. Fortunately, by the next morning, the river’s frozen over, and George and Christopher walk across and continue on their way.

Eventually they make it back to Dinwiddie in January and give him the reply. Again, won’t get into details, but Dinwiddie does give Washington that position in the Virginia militia of the British Army, which kickstarts his military career. When the French and Indian War starts, Gist helps Washington and his troops navigate the area. And decades later, when Washington’s leading the Continental Army across the Delaware River against the British…I have to wonder if he was thinking about crossing the Allegheny River almost 23 years to the day before.

By the way, if you’re in Pittsburgh, the island that Washington and Gist slept on is called Herrs Island. Or…Washington’s Landing.

Herr’s Island today.